Publication

The reconstruction of The Digital City, a case study of web archaeology

Authors: Tjarda de Haan and Paul Vogel

Twenty-one years ago a city emerged from computers, modems and telephone cables. On 15 January 1994 De Digitale Stad (DDS; The Digital City) opened its virtual gates in Amsterdam. DDS, the first virtual city in the world, made the internet (free) accessible to the general public in the Netherlands. But like many other cities in the world history, this city disappeared. In 2001 the city was taken offline and perished as a virtual Atlantis. The Internet celebrated its 45 years anniversary in 2014 and the World Wide Web its 25 years. The digital (r)evolution has reshaped our lives dramatically in the last decades. But our digital heritage, and especially the digital memory of the early web, is at risk of being lost, or worse already gone. Time for the Amsterdam Museum and partners to act and start to safeguard the digital heritage that was created and launched in Amsterdam. The project re:DDS, the reconstruction of DDS, was born.

Help! Our digital heritage is getting lost!

In 2003 the UNESCO made an emergency call: “The world’s digital heritage is at risk of being lost” (…) and “its preservation is an urgent issue of worldwide concern. (…) The threat to the economic, social, intellectual and cultural potential of the heritage – the building blocks of the future – has not been fully grasped” (1). The UNESCO acknowledged the historic value of our ‘born digital’ past and described it as “unique resources of human knowledge and expression”. Ninety percent of our records today are born digital, and therefore “the interpreting, preserving, tracing, and authenticating of these sources require the greatest degree of sophistication”.

De Digitale Stad (DDS; The Digital City)

DDS is such a digital heritage treasury from the early days of the web in the Netherlands. DDS is the oldest Dutch virtual community and played an important role in the internet history of Amsterdam and the Netherlands. DDS proved to be very successful. During the first weeks all modems were sold out in Amsterdam. In ten weeks’ time 12.000 residents subscribed. There was ‘congestion’ at the digital gates. Over the years the DDS user base of ‘inhabitants’ was growing: in 1994 there were 12.000 users, in 1995: 33.000, 1997: 60.000, 1998: 80.000 and in 2000: 140.000. The virtual city and its inhabitants produced many objects, ideas and traditions in new digital forms such as web pages (2), newsgroups, chat, audio and video.

DDS attracted international interest for the design it had chosen: DDS used the metaphor of a city to structure the still relatively unknown internet and made the users into ‘inhabitants’ of the city. Bringing culture and technology together.

Things were moving fast on the electronic frontier. “We have to deal with developments which to a large extent are unpredictable, elusive and ambiguous. DDS is in our view mainly an exploration and experiment with this unpredictability and ambiguity. (…) DDS is not only an experiment with computers, but an experiment with questions, problems and challenges posed by the emerging information and communication technology” (3). “The Digital City wants to contribute to the social debate about the ‘electronic highway'” (4).

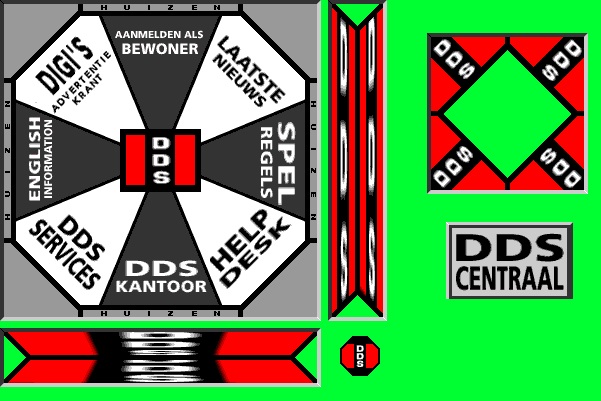

DDS followed the technological developments closely which resulted in several interfaces (cityscapes):

- DDS 1.0: 15 January 1994; all information and communication was offered in the form of a text-based environment (command-line interface; MS-DOS, Unix) in Bulletin Board System technology. The so called ‘Free-Nets’ in the United States and Canada where a major source of inspiration for the founders. Free-Nets were ‘community networks’, or ‘virtual communities’ developed and implemented by representatives from civil society (‘grassroots movement’). The metaphor of the city was reflected in the organization of the interface. There was a post office (for email), public forums, a town hall, a central station (the gateway to the internet) and squares to meet other visitors (5).

- DDS 2.0: 15 October 1994; entry to the World Wide Web with a website with a graphical interface and hyperlinks.

- DDS 3.0: 10 June 1995; introduction of the interactive ‘squares’ interface, the basic framework of the city’s structure. Each square had its own theme and character, and served as a meeting place for people interested in that particular theme. Visitors could find information and exchange ideas with each other. ‘Inhabitants’ could build their own ‘house’ (a web page), send and receive emails (worldwide!), participate in discussion groups, chat in cafes, take part in the ‘Metro’, vote etc.

The rise and fall of DDS

De Digitale Stad had grown out of an unique collaboration in 1993 between the Amsterdam cultural centre De Balie, the Hacktic Netwerk (a group of computer hackers who later became XS4ALL), and the local city council of Amsterdam (6). The election of the new city council (7) in March 1994 was the reason for De Balie to examine how ‘electronic media’ could boost the local political debate. The municipality of Amsterdam subsidized DDS from November 1993 to January 1995. In 1995 the structure of DDS was formalized by the creation of a foundation. In 1995/96 DDS was divided into two parts: a commercial part and a public area for the community. After a management buy-out in 1999, parts of the commercial DDS were sold. The virtual city, a public space on the World Wide Web, was taken offline in 2001. The collapse, for a lot of people a ‘culture shock’, was accompanied by some protest, some bickering and the formation of a counter-movement. But the protesting group largely fell apart because of internal turmoil and failed to prevent the city from disappearing.

The goals of the project re:DDS:

Then in 2011 the Amsterdam Museum initiated the project re:DDS and started defining the objectives. To consider the project as a success the museum aims to achieve the following goals:

- To give this unique (digital) heritage the place it deserves in the history of Amsterdam and to tell the story of DDS.

- To create a representative version of the internet-historical monument DDS in the Amsterdam Museum for people to visit and experience. (8)

- To start a pilot in digital archaeology and share knowledge in ‘The 23 Things of Web Archaeology’.

- To safeguard DDS in the collections of the heritage institutions for sustainable preservation.

Stages of the project

To start the project the museum laid out a roadmap:

- Launch of the open history laboratory and a living virtual museum.

- Bring Out Your Hardware & Finding Lost Data: crowdsourcing the archaeological remains (with The Grave Diggers Party as a kick-off event).

- The Rise of the Zombies: analyse and reconstruction.

- Flight of the Zombies: presentation of the Lost & Found and a reconstruction.

- Enlightenment: Let the Bytes Free!: Conclusions and evaluation.

Starting point

Fortunately we were able to draw information from many resources (9), since over the years quite a lot of (academic) research has been done on DDS. The Internet Archive had archived many web pages of the various websites of DDS and DDS ‘houses’ (web pages) of the ‘inhabitants’ since 1996, which were made available in the Wayback Machine. In 2004 the former DDS employees and the first web archaeologists in the Netherlands, Jeroen van Kan (10), Nina Meilof and Marleen Stikker (the first ‘virtual mayor’ of DDS), created a virtual open-air museum (11) for the tenth anniversary of the DDS with the archaeological remains they had collected. This pop-up museum inspired us to preserve the digital heritage of Amsterdam and to include DDS in the collection of the Amsterdam Museum.

Out of the box

The acquiring and preservation of digitally created expressions of culture has different demands than the acquiring and preservation of physical objects. This is a new area for the heritage field in general and the Amsterdam Museum in particular. The museum has to cross boundaries, and get out of its comfort-zone to break new ground in dealing with digital heritage. To seek out new technologies, and new disciplines. To boldly dig what the museum has not dug before. How to dig up the lost hardware, software and data? And how to reconstruct a virtual city and create a representative version in which people can ‘wander’ through the different periods of DDS and experience the evolution of this unique city? The challenge is: can we – and how? – excavate and reconstruct The Digital City, from a virtual Atlantis to a virtual Pompeii?

International forerunners

Internationally, there are a few great projects and initiatives that inspire us. With web-harvesting projects, such as The Wayback Machine (12) and GeoCities (13), current data are harvested (scraped/mirrored) and displayed or visualized. In recent web archaeological projects, such as the restoration of the first website ever, info.cern.ch by CERN (14), and the project ‘Digital Archaeology’ of curator Jim Boulton (15), the original data and software are found and reconstructed, and shown on the original hardware or through emulation techniques.

Challenges of web archaeology

In crossing the boundaries and dealing with new (born-digital) material the museum encountered the following challenges:

- Material: born-digital material is complex and vulnerable and has various problems. Due to the rapid obsolescence of hardware and software and the vulnerability of digital files, data could be lost or become inaccessible. Another problem has to do with the authenticity. With born-digital objects it is no longer clear what belongs to the original object, and what has been added later. And finally, important issues regarding to privacy, copyright and licensing form major questions.

- Division of tasks: who will take which responsibilities to retrieve, reconstruct, preserve and store born-digital heritage and make it accessible to the public? There is currently no central repository for tools (for example to read obsolete media), no central repository for sustainable storage or no comprehensive software library (for example to archive the old software, including Solaris, Windows, and MacOS).

- Methods: there is a difference between web-harvesting and digital archaeology. Web-harvesting is the equivalent of taking a snapshot of an live object, while we aim to recreate the object itself (or at least to create a representative version for people to access) from the ‘dead’ web.

- Approach: At present there is an alarming lack of awareness in the heritage field of the urgency (or funding) that our digital heritage is getting lost. The museum decided just to do it and act… (with lots of trial and error) and to start developing a roadmap to safeguard and preserve our born-digital past.

‘The 23 Things of Web Archaeology’

The reconstruction of the DDS constitutes a good case study for web archaeology. Not only to tell and show the story of this unique internet-historical monument of Amsterdam, but also – and more important – to raise awareness for and sustainable preserve our digital heritage for future generations. On the basis of this case study we try to answer the questions: how to excavate, reconstruct, preserve and sustainably store born-digital data to make it accessible to the future generations’?

Given the bias in our knowledge and the complexity, nature and scope of the matter, we need the expertise of a lot of institutions. Together with our partners we will explore the (im)possibilities. In cooperation we will (try to) reconstruct and document (for sure) our findings during the project in the form of 23 Things (16). In every ‘Thing’ we will explain our bottlenecks, choices and solutions. In addition, each partner will describe the state of affairs in the field of its expertise, and will illustrate this, where possible, with recent and relevant examples. In this way we share our joint experience and knowledge and in doing so we hope to lower the threshold for future web archaeological projects.

Data is the new clay, scripts are the new shovels and the web is the youngest layer of clay that we mine. Web archaeology is a new direction in e-culture in which we excavate relatively new (born-digital) material, that has only recently been lost, with relatively new (digital) tools. Both matter and methods to excavate and reconstruct our digital past are very young and still developing.

In ‘The 23 Things of Web Archaeology’ we will research the following issues:

- Born-digital material. What is born digital heritage? How does it work? How it is stored and used?

- Excavate and reconstruction. What are the current methods and techniques how to excavate and reconstruct born-digital material (the physical and digital remains and the context in which they are found)?

- Make accessible and presentation. Finally, we look at how we can interpret the remains and the context in which they are found and make it accessible.

What have we found so far?

In the meanwhile, we have been ‘digging’ and have excavated some great archaeological remains, like the original hardware, manuals, photos, video, audio, and… 54GB of data.

Grave Diggers Party

On Friday, 13 May 2011 the Amsterdam Museum organised a Gravediggers Party with the Waag Society in Amsterdam. A party with a cause. A party to re-unite people and collect lost memories, both personal and digital. “Help us dig up this unique city and be part of the first excavation work of the re:DDS!,” we invited former residents, former employees and to DDS kindred souls on our crowdsourcing platform and Open History Lab: http://hart.amsterdammuseum.nl/re-dds. “Look at your attic and/or hard drives and bring all servers, modem banks, VT100 terminals, freezes, disks, scripts, zips, disks, floppies, tapes, backups, log files, videos, photos, screenshots and bring all your memories and stories you can find!”.

Fifty enthusiastic (some international) cybernauts came along with full bags, hard drives and USB sticks to kick off the archaeological excavating. For three weeks the Waag Society served as an interactive archaeological site. There was a working space (17), where digital excavations were done, and a temporary exhibition was created where guided tours were given along the lost and found artefacts in the ‘Cabinet of Curiosities’.

After three weeks of digging we found some great artefacts. De Waag Society found and donated two public terminals. The terminals were designed by Studio Stallinga in 1994. Residents of the city of Amsterdam who did not have a computer with a modem at home, could make free use of these public terminals in various public places in Amsterdam. The terminals were located among others in De Balie, the Amsterdam Museum, the public library and the city hall.

Former system administrators brought in discarded servers they rescued from the trash. We excavated servers with exotic names such as Alibaba, Shaman, Sarah and Alladin. Their pitiful status: cannibalized (robbed of components, the costs were very high so everything was always reused) or broken or the hard drives were wiped (original data was erased and there was something else put over). A former resident donated one of the first modem banks. Another former resident sent a specially made radio play for DDS in 1994, ‘Station Het Oor’ (‘Station the Ear’). The play was made during the first six weeks after the opening of DDS. It was based on discussions and contributions of the first digital city dwellers. And we excavated thirty gigabytes of raw data, including backups of the squares, houses, projects. Furthermore we collected a huge amount of physical objects, like various manuals, magazines, photographs, videotapes and an original DDS mouse pad.

Freeze!

As cherry on the cake we excavated the most important and unique artefacts, namely the three DLT tapes, titled: ‘Alibaba freeze’, ‘Shaman (FREEZ)’ and ‘dds freeze’. We think this is the ‘freeze’ of DDS of 1996. On 15 January 1996 DDS, the ‘ten week experiment that got out of hand’, existed for exactly two years. For the second anniversary of DDS, the pioneers of the first social network in the Netherlands sent a digital message in a bottle: “In the past two years, the Digital City has been focused on the future. This anniversary is a good time to take a moment to reflect on what happened the last two years in the city. High-profile discussions, large-scale urban expansion, people coming and going, friendships, loves and quarrels, the Digital City has already a long history. Three versions of the Digital City have been launched in two years.

People come and go. Trends come and go. Houses are rigged and decorated. But where are all digital data kept? Who knows about 5 years how DDS 3.0 looked like? The Digital City will be ‘frozen’ on Monday, January 15th at 18:00 o’clock. A snapshot with everything the city has to offer will be stored on tapes and will be hermetically sealed. The tapes with the data, along with a complete description of the programs and machines the city is run with and upon, will be deposited in an archive to study for archaeologists in a distant future” (18). The tapes however were never deposited, and were more or less forgotten. Fortunately for us they were rediscovered a few weeks after the Grave Diggers Party.

The tapes came (of course) without the matching tape reader. After a frantic search an ‘antique’ tape reader was found in the National Library of the Netherlands in Den Hague, where it was used as … a footstool. The Library, partner of the project, donated the tape reader to the project. In big excitement we started digging. But after two nights of reverse engineering the tape reader and the tape, we only found 70MB where we hoped to find 3GB. We were pretty disappointed. All sounds coming from the tape reader (tok tok, grrrrrr, beeeep) gave us the impression that containers of data were being flushed, and we thought the city had evaporated. We were puzzled. Had there ever been more data on the tape? Is this the ‘freeze’ we had hoped to find? What was broken, the tape reader or the tapes. Or both?

After our failed attempts to read the tapes and our bloodcurdling reverse engineering experiences (dismantling the reader and manually rewinding a tape), we called the Computer Museum of the University of Amsterdam for help. Would they be able to read the historical data of DDS of the tapes? Engineer Henk Peek started to excavate immediately. Only a few weeks later he mailed us a status report:

I’ve excavated about 11 Gigabytes of data tapes.

It looks very positive!

We have made enormous progress in what we call our ‘slow data project’. It is time for the next step. We will start with the reconstruction and share our knowledge with our pioneering partners now, bit by bit, byte for byte!

In the meanwhile the Amsterdam Museum decided to bring the history of DDS to life in the museum. We are proud to announce that DDS has been included in the permanent collection. The audience can ‘experience’ DDS in the Amsterdam Museum by taking place behind an original DDS public terminal and watch television clips from 1994 about DDS. And, in the nearby future hopefully, people can interact with our born-digital heritage and take a walk through the historical digital city.

To be continued

Go to our open history laboratory and living virtual museum:

Partners

We would like to thank our partners for their enormous contributions to the project re:DDS. Our partners are (till now): Amsterdam City Archives; Digital Heritage Netherlands; Dutch Cultural Coalition for Digital Durability; Karin Spaink, independent researcher; Old inhabitants, (ex) DDS employees and DDS affiliated web archaeologists; Dutch Computer Heritage Foundation; International Institute of Social History; National Library of the Netherlands; Netherlands Institute for sound and vision; Waag Society; University of Amsterdam, Professor of Heritage and Digital Culture Julia Noordegraaf and dr. Gerard Alberts; University of Amsterdam Computer Museum.

Author Biographies

- Tjarda de Haan studied contemporary history in Amsterdam and Berlin. Then worked for several new media companies, including De Digitale Stad. Now she works as a guest e-curator and web-archaeologist for the Amsterdam Museum and her own agency Bits and Bytes United.

- Paul Vogel has been a senior Unix engineer for many years for several companies, including DDS. He works as a volunteer web-archaeologist for the Amsterdam Museum.

About the Amsterdam Museum

The Amsterdam Museum is the city museum of Amsterdam, a meeting place for anyone who wants to learn more about the city. In the monumental Amsterdam Museum building you will discover the story of Amsterdam through a large number of masterpieces, such as an aerial map from the Middle Ages and Breitner’s The Dam. See, read about, hear and experience how the city has developed in the Amsterdam Museum. The website: http://www.amsterdammuseum.nl/

Correspondance contact information: T.deHaan@amsterdammuseum.nl

Notes

- UNESCO. (October 15, 2003). Charter on the Preservation of Digital Heritage. Retrieved from http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=17721&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html.

- The web started with the proposal for “a large hypertext database with typed links” written by Tim Berners-Lee, an independent contractor at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in March 1989. He wanted to create a document retrieval system. With the hypertext a reader could access texts on a remote computer via references (hyperlinks). Several names passed before the name the World Wide Web was chosen. Alternatives were the Information Mesh, The Information Mine (turned down as it abbreviates to TIM, the WWW’s creator’s name) or Mine of Information (turned down because it abbreviates to MOI which is “Me” in French). In 1990 sir Tim Berners-Lee had built all the tools necessary for a working web: the HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP), the HyperText Markup Language (HTML), the first Web browser (named WorldWideWeb, which was also a Web editor), the first HTTP server software (later known as CERN httpd), the first web server. He created the very first Web pages ever: http://info.cern.ch, that described the project itself. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_World_Wide_Web.

- Schalken, C.A.T., Tops, P. W. (1994). De Digitale Stad, het eerste jaar. Tilburg: Katholieke Universiteit Brabant, page 15.

- Hinssen, Peter. (1995). Life in the digital city. Wired, Issue 3.06. Retrieved from http://archive.wired.com/wired/archive/3.06/digcity_pr.html.

- Configuring the digital city of Amsterdam. Social learning in experimentation, by M.J. van Lieshout (TNO, 2001), page 31. http://reinder.rustema.nl/dds/lieshout/configdigitalcity.pdf.

- As a sight-effect DDS proved to be very good for the cyber-reputation of the city of Amsterdam. CNN broadcasted a report from Amsterdam ‘Digital Expansion in The Netherlands’ in 1997 in the program ‘The CNN Computer Connection’. Dick Wilson reported enthusiast: “Amsterdam is a city building on its rich past to create a high tech future. For hundreds of years the city of Amsterdam has been a center of commercial trade, art and education. Now it’s helping point the way in the information revolution too. For 2 reasons. Holland has the highest rate of new internet connections in Europe, and free or low cost internet access and email service for everyone who wants it”. http://hart.amsterdammuseum.nl/71513/nl/project-re-dds-ii-waarom-dds Manuel Castells, the Spanish sociologist associated with research on the information society, communication and globalization, referred to DDS as “The most famous citizen computer network. (…) A new form of public sphere combining local institutions, grassroots organisations, and computer networks in the development of cultural expression and civic participation”. The Internet galaxy: reflections on the Internet, business, and Society, by Manuel Castells (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2001).

- “The functioning of democracy was one of the fundamental concerns for the experiment. In the wake of the 1994 elections the DDS was, for as far as the City of Amsterdam was concerned, designed as a democracy enhancing tool. On the main square in DDS, the first screen that appeared after signing in, option 9 was the election center “Verkiezingscentrum”. The DDS provided the citizens with all the background information on topical issues to help citizens of the Digital City form their opinion. One was encouraged to discuss policy information with others and you could even contact your local representative by email if you felt the need. (…) Discussion was to take place in any of the USENET newsgroups in the dds.* hierarchy, most of which were named after the different issues that were relevant for the municipal elections”. the author Reinder Rustema also states that “In practice there was no response although DDS employees installed email on the computers of civil servants and politicians. (…) There were no open discussions, even a discussion on DDS itself was not possible”. http://reinder.rustema.nl/dds/rise_and_fall_dds.html

- If possible we would like to reconstruct DDS and create a ‘4D collection’ (height, width, depth and time) in which people can switch between ‘multiple-points-in-time’ and experience the evolution of this unique virtual city.

- http://www.delicious.com/re_dds/

- Confronted with the loss of the virtual city web archaeologist Jeroen van Kan wrote: “Miraculously there are more remains preserved from most historic cities than from DDS. There are more remains of Athens and Rome than from DDS, which is very surprising for a city that only has existed ten years and has just recently disappeared. (…) That DDS, as quickly and as thoroughly, has disappeared says something about the phase in which the net finds itself. Similar to that of the television in the sixties and seventies. Tapes were then systematically reused, so much historical material was destroyed. The same is happening with the net, only to a much more severe degree. Our culture has become even more volatile, more inclined to throw away everything for which we have no immediate need and is less attached to sustainability than previous decades. The web page as equivalent to the hamburger wrapping of a fast food chain”. http://www.vankan.dds.nl/dds/

- http://www.vankan.dds.nl/dds/verjaardag.html

- The Wayback Machine of the Internet Archive (http://archive.org/web/) is the first digital archive that archives web pages and them accessible via a web interface since 1996. The Wayback Machine: Preserving the History of Web Pages door ForaTv https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JsL1TADosN0. The Internet Archive Documentary, door Doc Streams in 2014 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1WxGDOeS-s4. View the old versions of DDS in the Wayback Machine: http://web.archive.org/web/*/http://www.dds.nl. View the old DDS ‘houses': http://web.archive.org/ web/*/http://huizen.dds.nl/.

- GeoCities began in late 1994 and offered users, like DDS, the ability to create a website for free. The owner Yahoo took the website offline in October 2009. Several organizations committed to save the data: The Archive Team (http://www.archiveteam.org/index.php?title=GeoCities). The Internet Archive (http://archive.org/web/geocities.php). The artist duo Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenschied made a blog and exhibition ‘One Terabyte of Kilobyte Age’ (http://oneterabyteofkilobyteage.tumblr.com/). Richard Vijgen developed an installation with an interactive visualization ‘The Deleted City’. http://www.richardvijgen.nl/#deletedcity and http://vimeo.com/user8644054 and http://deletedcity.net/

- CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research in Geneva, restored the first website in the world in 2013: http://info.cern.ch/ and http://first-website.web.cern.ch/.

- The project ‘Digital Archaeology’ of curator and co-author of the book ‘Digital Revolution: An Immersive Exhibition of Art, Design, Film, Music and Video Games’ (Barbican Art Gallery, 2014) by Jim Boulton and others. http://digital-archaeology.org/category/exhibition/, http://www.barbican.org.uk/digital-revolution/ and https://www.youtube.com/user/DigitalArchaeology.

- “The 23 Things of Web archaeology” is based on the Learning 2.0 – 23 Things, http://plcmcl2-things.blogspot.nl/, program of Helene Blowers and inspired by the many sites of the 23 Things that followed.

- The tools used were: computers (excavators), storage (buckets), UNIX commands and mice (spades, pick-axe, trowels), scripts (metal detectors), USB (find bags) and Metadata (find cards).

- http://web.archive.org/web/20100830120819/http://www.almedia.nl/DDS/Nieuws/freeze.html.

This article is published in “Data Drift. Archiving Media and Data Art in the 21st Century” (October 2015), published by RIXC, LiepU MPLab, http://rixc.org/en/acousticspace/all/ and Amazon.